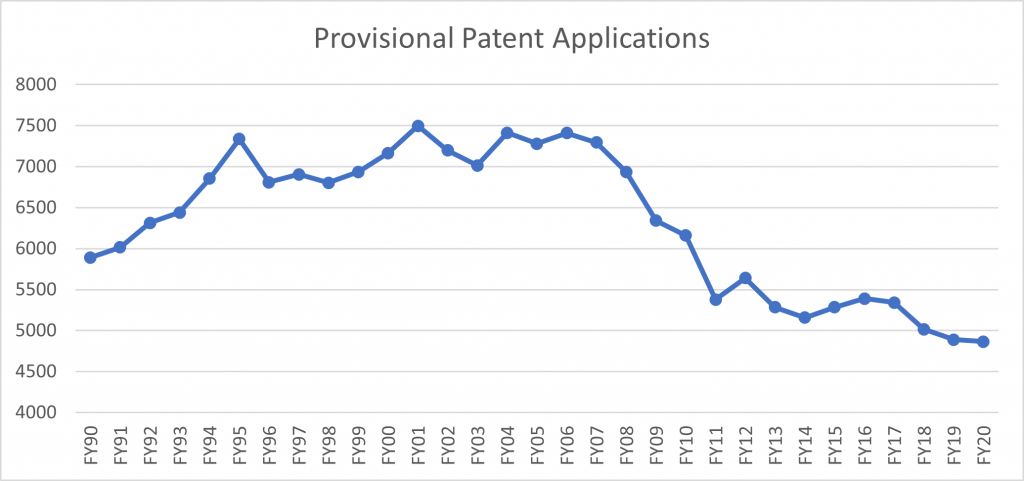

There has been a steady decline in innovation in Australia since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2007. This is clear from the Australian Patent Office data which shows the number of provisional patent applications filed in Australia. The chart below displays the number of filings of provisional patent applications per fiscal year from FY90 to the present.

The data clearly shows that up until FY95, there was growth in provisional patent filings. Provisional patent filings then plateaued until the GFC. After the GFC there was a significant drop in filings and that volume has never recovered.

A provisional patent application is a popular first step to patent protection and has a life of 12 months. Within the 12 months, an Applicant must decide whether or not to continue with protection of the invention. If the invention is worthy of continued protection, the most popular approach is to file an international application through the Patent Cooperation Treaty, from which patents can be obtained in multiple countries. A provisional patent application allows the Applicant to flag their earliest priority date to the world so they can publish, make, use and sell the invention without affecting their patent rights. Once an invention is publicly disclosed, the right to obtain protection is essentially lost except for a few countries which have limited, short-term grace periods.

Filing of a provisional patent application is an indication that an innovation is, in the mind of the innovator, worth protecting. Furthermore, in most cases, a patent attorney has looked at the innovation and agreed that there is a good chance of valid protection through the patent system. Thus, it is fair to say that the number of provisional patent applications filed is a good indicator of innovation. To put it another way, an increasing number of provisional patent filings indicates an increase in innovative activity, whilst a decreasing number indicates a decline in innovative activity. From the data above, we can conclude that innovation in Australia was on the increase until the mid-1990s and declined significantly after 2007.

The number of filings of provisional patent applications is a good indicator of domestic economic activity, whereas the total number of patent filings is not useful. This is because about 90% of patent filings in Australia originate overseas (https://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/ip-report-2019/patents). This also indicates that Australia is a net importer of technology. This has been brought into sharp focus in 2020 with the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. What we have seen is that Australia is heavily reliant on importing technology. Our ability to develop our own solutions to difficult problems has been impaired by the steady decline in innovation. This is not a surprise but the degree to which this has occurred, as seen in the chart above, is surprising.

There are many ways to evaluate economic sentiment, such as GDP growth, housing market growth, business sentiment index, or the consumer confidence index. These can provide an indication as to how the economy is tracking and if economic growth is declining or static. The main problem is that these measures are lag indicators. The number of provisional patent filings is a current indicator of sentiment, at least in the innovation space. The chart suggests that sentiment has been negative for over a decade.

It is also worth noting that a granted patent has a maximum life of 20 years from the filing date (21 years including the one-year provisional patent term). However, most patents are not maintained that long as most are allowed to lapse at around eight to ten years from filing. The least valuable patents are allowed to lapse earlier, and more valuable patents are maintained longer. It can be argued that this is an indicator of how long it takes for the benefit of significant innovation to be lost from the economy. Looking at the data, the decline in innovative activity that started around 2007 is expected to have an impact sometime this year. With the added impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first recession in 29 years is unsurprising.

What we conclude from the current situation and the historical data is that we need to incentivise innovation. Perhaps this is already happening to some extent as necessity drives innovation. Since March 2020, there have been a number of patent filings directed toward COVID-19-related inventions. A search for “COVID” on the Australian patent database, discloses 15 results at the time of writing. These are either provisional, standard or innovation patent applications. Some examples of the results include therapies to reduce the effects of COVID-19-like infections, QR code scanners, machine learning to track COVID-19 transmission, hand sanitising stations and a laser to attenuate the virulence of the virus.

We have also seen a subtle shift from a market-driven economy to a more directed economy. This is exemplified by Federal Government policies to shift education emphasis towards science and engineering. As patent attorneys who work at the cutting edge of innovation, we are encouraged to see the measures taken to direct more students into STEM, however we also recognise that good innovation requires both creative and analytical thought, hence an over-emphasis on STEM may not achieve the hoped-for increase in entrepreneurial activity.

The data leads us to the question: what should businesses be doing with their intellectual property during times of economic difficulty? Some thoughts can be found in looking at what happened during the GFC. Hard data is hard to find, but anecdotally we noticed an increase in oppositions and litigations at the same time as a decrease in new patent filings. This suggests that in periods of economic stress there is a tendency to protect what you have rather than generate new IP. This may be sensible, but only as long as businesses pivot back to IP generation after the period of economic stress passes. What we have seen from the past is that this did not happen. It is predicted that the Australian economy will recover quickly from the recession caused by COVID-19, so perhaps a different strategy is needed. Businesses that thrive will be those that have pivoted to new technologies and protected their new innovations. This is particularly important during the years following a recession when the economy is recovering. Being that a patent can have a term of 20 years, a business that reacts quickly to a changing environment and identifies an opportunity can obtain and maintain a significant competitive advantage by protecting their innovations.

There are multiple examples of Australian technology businesses with significant patent portfolios that have helped them grow despite the decline in home-grown innovation. This includes companies such as CSL, ResMed, Orica and Cochlear, just to name a few. These companies have continued to develop new and improved ways to ensure they remain competitive both now and in a post-COVID-19 (or COVID-19-managed) economy.

Every business has an opportunity to beat the current negative trend. It is important for a business to protect and enforce their existing IP rights, but it is equally important to continue to innovate and protect those innovations, even during times of economic difficulty. Companies need to look to their IP to give themselves the best chance of success against competitors, and to put “the year of COVID-19” in the rear-view mirror.