This case highlights the importance of construing claims using plain English meaning and not adding a “gloss” to the language of a claim.

Background

The primary judge held in Davies V Lazer Safe Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 702 that the respondent’s product did not infringe the Patentee’s claims of Australian Patent No. 2003229135, entitled “A Safety System” (the Patent).

The Patent

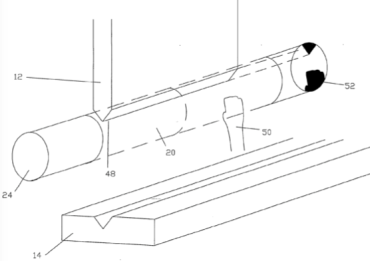

The Patent relates to a safety system for a machine that bends sheet and plate metal, such as a press brake. The machine detects the presence of an obstruction in the path of a moving part, which bends the metal (see item 12 below), and stops the machine. An obstruction in the path of the moving part might be important, such as an appendage of the body, for example.

The Focal Issue

The appeal centred around the construction of two integers (1.5 and 1.6) of claim 1, reproduced below (emphasis added).

(1.5) a processing and control means arranged to receive image information from the light receiving means and thereby recognise the presence of one or more shadowed regions on the light receiving means cast by obstructions in the region;

(1.6) wherein the illumination of the region is such that the processing and control means has sufficient image information to determine the boundaries of the or each shadowed region and control movement of the part dependent on said image information.

The primary judge construed the term “recognise” in integer 1.5 as not merely detecting a shadowed region, but “recognises, that is, compares the shadowed region detected with what is previously known – the shape of obstructions”. The primary judge held that this construction was consistent with and supported by the body of the specification, which essentially describes a comparison step (p7 lines 9-11 of the Patent).

At paragraph 40 of the decision, the full court disagreed with the primary judge’s construction of integer 1.5, stating that “No language in claim 1 indicates that the words ‘image information’ and ‘recognise’ are to be understood as inviting a comparison between the detected shadowed region and a previously known shape or obstruction.” The full court further stated that “recognise the presence of one or more shadowed regions” indicates that “recognise” is to be understood as “to perceive as existing”, rather than as inviting comparison with something previously known. Put simply, the presence of the shadowed region is all that is required, and nothing in claim 1 justified a comparison step.

The full court held that the primary judge added a “gloss” to the language of the claim by incorporating the concept identified in the body of the specification. Importantly, it was noted that although the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the scope of the claimed monopoly by affixing to the words of the claim, glosses drawn from other parts of the specification. The full court noted that the principles of patent and claim construction are well established under Australian law (paragraph 42), citing several cases, but in particular, Welch Perrin at 610.

The full court noted that the specification is loaded with non-definitive language such as “by way of example” and “the embodiment shown”, to not constrain the scope of the claims. This is indicative of the view that “the body of the specification does not there purport to set out the scope of the invention.”

Regarding integer 1.6, the primary judge made a first and a second construction. The full court rejected the first construction, however agreed with the second construction:

…the proper construction of claim 1 requires the boundary determination of an obstruction claimed by recognising a realistically substantial portion or part of the shadowed region, so as to determine a sizable portion of the outline or shape of the obstruction, in contrast to a dot, spot, point or edge of any such region.

Turning to infringement, the full court held that on the basis of the correct construction, the primary judge ought to have found that integer 1.5 was present in Lazer Safe’s allegedly infringing product. However, the full court found that Lazer Safe’s product does not determine the boundaries of the shadowed regions and therefore does not have integer 1.6. Thus, the claims of the Patent were not infringed. As the non-infringement finding by the primary judge was upheld, the cross-appeal was dismissed. Despite the full court’s finding of non-infringement, the interpretation of integer 1.5 was broader than that of the primary judge.

This decision highlights the importance of careful claim drafting and also the importance of construing claims using the plain English meaning / dictionary definition of a word or phrase. Although these principles have been well established under Australian patent law, it can sometimes be difficult to not be influenced by embodiments or specific examples described in the specification. When construing claims, the specification should be relied upon only when the meaning of a word or phrase in the context of the specification is ambiguous.